Embracing Curiousity and Parsing 40-Year-Old Soviet Digital Imagery

Halley’s Comet is likely the most well-known comet, and possibly the most well-known astronomical object that isn’t a star, planet, or moon. As many reading this will know it arrives and is visible from Earth once every 76 years. The last time it arrived, a group of countries worked together to form a ‘flotilla’ of space probes and perform a lot of science and observations of the comet.

A week or so ago, I happened to remember this, and in particular that the last two Soviet probes to Venus both happened to go to the comet as part of this effort. The notable thing to me from the Wikipedia page and others about these probes is that they both carried a television camera with them, and had imaged the comet with this camera.

Image of Wikipedia

I’ve never seen this footage online, and I have never seen a video of a comet, so I figured that I’d spend an evening or two putting this together from the data.

The data itself is (are?) located on an arcane University of Maryland-hosted NASA site, called the Small Body Node. https://pds-smallbodies.astro.umd.edu/data_sb/missions/ihw/index.shtml. From the site and from some of the supporting documentation, it is clear that many scientists spent much of the 80s and 90s going through this data, cleaning it up, and writing about it. I wasn’t really concerned with science though - I just wanted a video of a comet.

I downloaded the data and cracked open the archive. Inside each instrument’s dataset are a set of folders organized however they felt like leaving it when uploaded in 1995. For Vega 2, the data are organized by what post-processing has been applied. To start, I used the data in the main folder.

The images here had (and still have) a .img file extension. Opening the .lbl or .hdr metadata files didn’t really help me out with figuring out how to open the images for viewing, but they would be useful later. Some googling told me that the images should either be in Erdas Imagine format or from an obscure old Windows competitor called GEM.

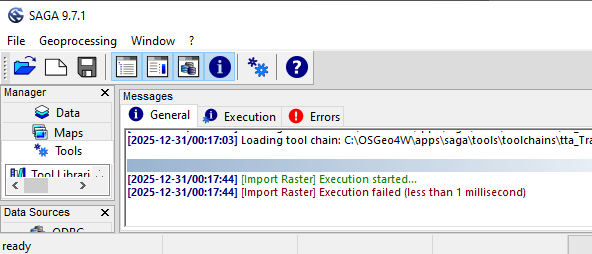

I’m familiar with Erdas from my university days, so I cracked open my copy of SAGA GIS and attempted to import the files as this format.

Image of SAGA GIS, showing a failure message

No dice.

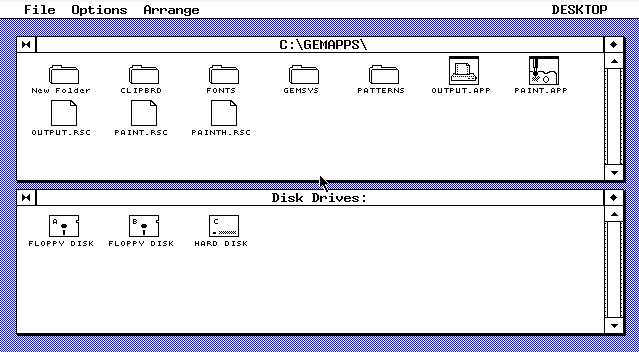

Next, I installed DOSBOX-X to give me a good DOS platform to work from, and installed GEM onto it. GEM is an interesting OS for the weird cross between Windows 3.0 and Macintosh it looks like. It’s got the ever-present file menu/desktop view that Windows 3 has, but the menu bar feel of Mac. I might have to revisit it in the future.

Image of the GEM desktop

GEM really didn’t like .img files. Loading one into GEM Paint locked up the system bad enough to need a full reboot regardless of how I tried to do it.

The last thing I could think of was that the documentation included in the files mentioned that this was supposed to be in FITS format. As I learned while writing this blog post, FITS is an image format allowing for the wide variety of wavelengths and supporting data that astronomical imagery needs. I googled FITS format reading, and found that both GIMP and Python (through the Astropy package) should support it. Opening in GIMP did nothing, and neither did Astropy - many dead ends here.

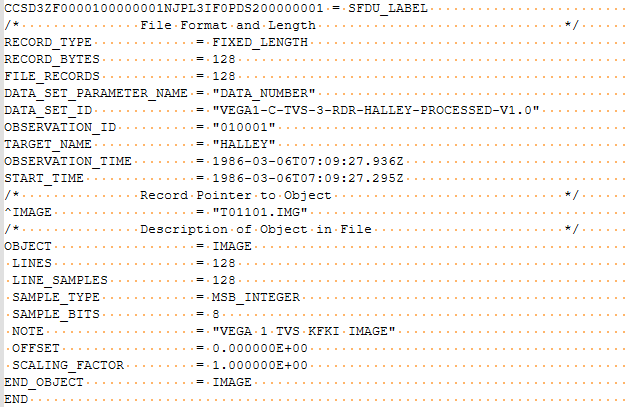

So, it seemed that this wasn’t going to be as easy as I hoped and I was going to have to parse this myself. Luckily, the header/label files I mentioned earlier could help out. The label file told me that the image data was stored as 8-bit integer data, using most-significant bit encoding, and with a 128-length line.

Image of the label file

Using a hex editor, I verified that there was nothing that looked like a header in the data itself, and wrote a script to parse out lines of 128 integers from each image, and write those lines as image data to frames of a GIF to see if this really was a television recording. Note that the images here are provided at original 128px by 128px size, except where they were “big” (my name, the actual files aren’t differentiated) 512px images.

Now that I had a script that worked, I looked around the various folders included in the dump. There are a number of versions included, but the “post” version is the most interesting (IMO). This contains a set of smaller and larger files, with the larger files being higher resolution, and all of them having notably higher quality than the rest of the dataset. Since this is just the footage they got after the closest approach, I can only assume that they took the most time to get the exposure right.

Longer, post-encounter GIF

Most of the images were taken about 30 seconds apart, so the probe recorded more of a timelapse than it did a realtime broadcast. There are some larger gaps here and there, so I made another script (included in the Github) that adds extra frames to scale the animation accordingly.

Full set of images. Countdown is to encounter time, in seconds.

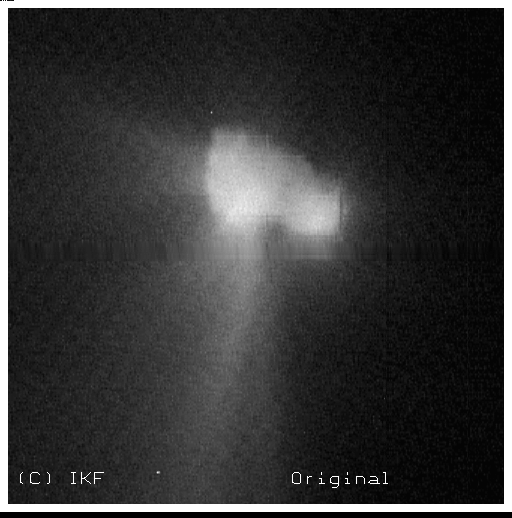

I also found the frame from Vega 2 that tends to make it to any articles about the Vega spacecraft. This frame was cleaned up by Abergel, J. et al as part of their 1997 article.

The original (or at least the version still around in the data looks like this:

And a “smoothed” version is also provided. I rotated it to match the version usually provided online.:

The most striking thing to me about all of these images was how cool it is to see what seems to be a flyby of the comet, and also how little exists about this. It seems to me that this animation (or a further retouched version) should be the first thing that anyone sees of Halley’s Comet, but as far as I can tell it has never been shared in this way.

All I can say is that if you’ve ever seen some kind of weird loose end on some Wikipedia rabbit hole you’re on, you too should track down whatever little source data is hanging around out there and look at it for yourself.

If you want to look at my processed versions, a .zip is available here